What is Gandhi’s Concept of Swaraj? Explaining Gandhi on Swaraj

Gandhi’s concept of Swaraj is defined as a ‘model code of conduct which points men on the path of their duty,’ path of control over desires, and the path of ‘mastery over their minds and passions.’ Swaraj implies the elevation of a personal moral being to limit indulgences and sees happiness as largely a mental construct. Otherwise, what did Gandhiji mean by Swaraj? Find out more about Gandhi on Swaraj and independence, democracy and the future of India.

“I am not interested in freeing India merely from the English yoke. I am bent upon freeing India from any yoke whatsoever. I have no desire to exchange king log for king stork. Hence for me the movement of Swaraj is a movement of self purification.”

Selections from Gandhi by Nirmal Kumar Bose, 1948

Gandhi on Swaraj: What does Swaraj Mean?

First, to achieve the state of ‘Swaraj,’ one has to live a life of simplicity and should not have greed for wealth and power. For Gandhi, high mental intellect is not possible unless one stops running after material life. Basically, he wanted to create a world where an individual followed agricultural labour under a sustainable village ecosystem and lived independently. Gandhi divided ‘Swaraj’ in the following ways:

- National Independence

- Political freedom of the individual

- Economic freedom of the individual

- Spiritual freedom of the individual or ‘self rule.’

Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of Swaraj confirms his firm commitment to moral individualism. The term ‘Swaraj’ literally means ‘self-rule,’ ‘self-government,’ ‘self-determination’ or ‘independence.’ This term became popular during India’s struggle for independence from the “British Colonial Rule.”

Gandhi’s Concept of Swaraj and Independence

Gandhi argued that ‘Swaraj’ did not simply mean political independence from the foreign rule; it also implied the idea of cultural and moral independence.

If a country is politically independent but culturally dependent on others for choosing its course of action, it would be devoid of ‘Swaraj.’ Swaraj does not close the doors of learning from others, but it requires confidence in one’s own potential and decisions. Gandhi thought of ‘Swaraj’ as a system in which all masses will have a natural affinity with their country and they will readily collaborate in the task of nation-building.

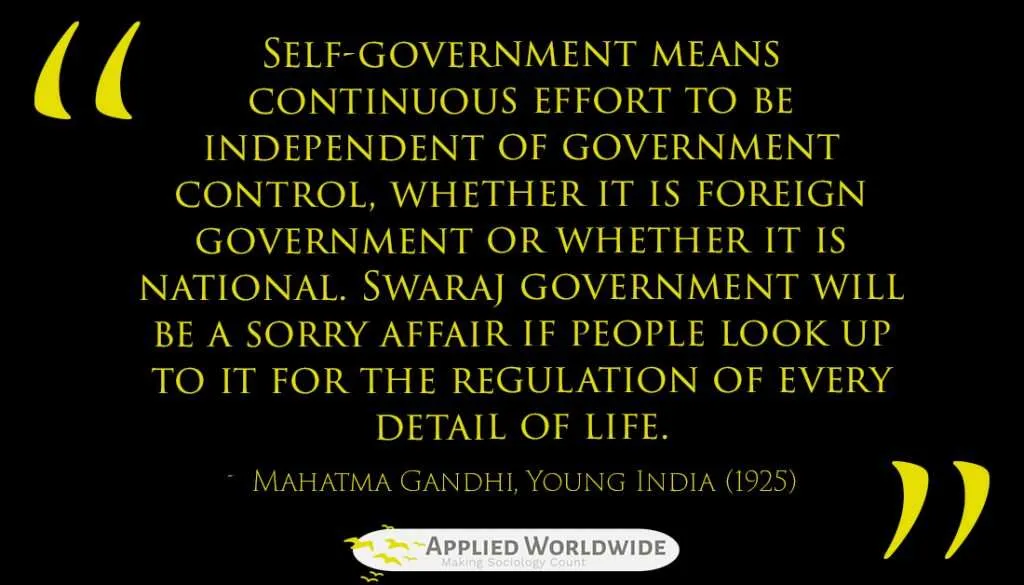

‘Swaraj’ or self-government rules out people’s dependence on government. This applied even to their own government. Thus Gandhi writes in Young India (1925): “Self-government means continuous effort to be independent of government control, whether it is foreign government or whether it is national. Swaraj government will be a sorry affair if people look up to it for the regulation of every detail of life.”

Gandhi on Swaraj and Democracy

First, Gandhi’s concept of Swaraj exemplifies his vision of a true democracy. Under this system, people will not merely have the right to elect their representatives, but they will become capable of checking any abuse of authority. In his own words, mere withdrawal of the English is not independence. Furthermore, Independence means the consciousness in the average villages that they are the maker of their own destiny, that they are their own legislator through their own representatives.

The real ‘Swaraj,’ he felt, will not come by the acquisition of authority by a few but by the acquisition of the capacity by all to resist authority when abused. Equally important, ‘Swaraj’ is to be attained by educating the masses to a sense of their capacity to regulate and control authority. Economic freedom of the individual is the third dimension of ‘Swaraj.’ Economic Swaraj stands for social justice, it promotes the good of all equally including the weakest and is indispensable for a decent life.

Gandhi on Swaraj and India’s Economic Future

For Gandhi, India’s economic future lay in the adulation of the ‘charkha’ (spinning wheel) and ‘khadhi’ (homespun cotton textile). If India’s villages are to live and prosper, the charkha must become universal. Rural civilization argued Gandhi, “is impossible without the charkha and all it implies, i.e., the revival of village crafts or cottage industries.” As a votary of purity of means as well as ends, Gandhi tried to assert that we must rely on non-violence or ahimsa for the attainment of political self-government as well as individual self-government.

Gandhi elaborately dwells on the principle of nonviolence or ahimsa as the way to transform individual character. Also, as the guiding principle of political struggle. He demonstrates the superiority of non-violence over violence ‘at least in the majority of the cases.’ He asserts that the force of love and pity is infinitely greater than the force of arms. The principle of non-violence is founded on soul force (will power) while violence was founded on physical force.

The qualities of soul-force are akin to love-force, compassion force, the force acquired by self-suffering and moral force. All these forces become operative when mind is able to control itself and the passions. An individual endowed with these forces would be naturally inclined to adopt the technique of nonviolent resistance (Satyagraha) as his method of political struggle.

More Indian Philosophy and Society from Applied Worldwide

Applied Worldwide is happy to publish a blog series applying Indian philosophical ideas to the current context. Our Indian Philosophy and Society series is written by Adhrish Chakraborty and includes articles using the philosophies of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo.