As a sociologist, I hardly ever talk about my experience in the United States Navy. There is a lot that sociologists do not understand about being a veteran, which is why I am happy to publish this interview with Applied Worldwide.

Serving in the military has given me a great deal of insight that I am able to use in my sociological work, but these experiences are simply unrelatable to a majority of my sociology colleagues. With that said, I do still face misconceptions about the military, my involvement, and what it all really means. For example, I once came across rumors in a professional environment that I was missing a leg because I never wear leg-exposing apparel. Another, more common, example is when I am thanked or honored on Memorial Day or the Fourth of July, neither holiday in which I am owed any gratitude.

Please be advised that the following is an edited transcript of an interview I gave an undergraduate student in 2013. These experiences are my own and are by no means representative of all veterans’ experiences.

What were the dates of your enlistment, training, and deployment(s)?

My total enlistment was August 24, 2007 to August 23, 2011. After my first six weeks of basic training I attended about three months of what is called A-School. A-school is mostly classroom work learning about your future job. My job was called “Aviation Boatswains Mate” so we mostly learned about different types of aircraft and that sort of thing. Early 2008 I was assigned to the USS Carl Vinson, the ship that I would be stationed on for the remainder of my enlistment.

The Carl Vinson was in the docks being rehabbed so I was not actually doing the job that I had signed up for nor did I have a chance to get any of the qualifications that I needed to do my job. Six months into being stationed on the Vinson, I was sent on “Temporary Assigned Duty” to the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower for, from what I remember, two to four weeks. This was a chance for me to gain some experience and qualifications in my job. My first actual deployment came in January of 2010. This deployment was a peace mission called “Operation Unified Response,” which was an emergency response to the earthquake in Haiti.

The Carl Vinson was the first US naval responder when the tragedy occurred. The deployment was about six months and we came back state side in the summer of 2010. We were in port at Coronado Island in San Diego for about another six months and would get redeployed to the Persian Gulf sometime at the end 2010. This deployment was a joint mission between “Operation Enduring Freedom” and “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” Once again it was approximately a six month deployment and I came back stateside about two months prior to my separation from the military in 2011.

What branch/division were you a part of?

I was a part of the US Navy stationed aboard the USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70). I was a part of the “Air Department” in the “V1 Division.”

There are a ton of different Departments on an aircraft carrier, the Air Department deals with everything related to Flight Operations. The V1 division was the division that ran the Flight Deck. There were five total divisions in charge of different aspects of Flight Operations.

- V1 – Flight deck

- V2 – Mechanics who worked on the catapults and arresting gears. They did all the maintenance that made it possible for planes to take off and land.

- V3 –When the planes were not flying or if they needed to be worked on, they were moved below the flight deck into a hangar bay on a giant elevator. People in V3 were in charge of the Hangar Bay

- V4 – In charge of fueling the planes

- V5 – These folks did all the paper work (and probably other stuff, but I did not see them very often)

Where specifically did you serve? US or overseas?

My basic training was in Great Lakes, Illinois, outside of Chicago and my A-school was in Pensacola, Florida. My first station on the Vinson was in Newport News, Virginia. Once the ship was operational, we moved to Norfolk, Virginia. After we responded to Haiti we moved homeports to Coronado Island, California. My first Temporary deployment on the Eisenhower was just a training mission so we remained near Florida.

The peace mission to Haiti took us from Haiti to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, then around the bottom of South America back up to Lima Peru and eventually to California. The mission to the Gulf took us to the Southeast Pacific to South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and eventually to the Persian Gulf. We would go back and forth between the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea depending on the mission. At the end we returned to California.

What was the training like? How long was it for?

Training was surprisingly simple, at least from a physical standpoint. Basic training was more about how to clean and fold clothes. It sounds silly but with very little room to store things on a ship, efficiency and cleanliness is important. We did some exercise and had some physical tests, but it really was not as difficult as it might be made out in pop culture.

The really “hard” aspect of boot camp was the structure, just having someone else make all of your decisions. We received qualifications in how to shoot a 9mm and a 12 gauge shotgun. The most surprising thing for people is how little we swam considering we would spend so much time on the water. To many others’ surprise, the only swimming test required us to jump off a platform and swim to the other side of a normal sized pool.

The technical school was sort of challenging because it required a lot of studying and class time. All the exams were multiple choice and pretty easy, but I could see how some people struggled if they got test anxiety or weren’t very good at exams. That part was pretty easy for me.

Actual on the job training was better. You are required to put a big orange “T” on your headwear, so everyone knows you are in training and you have to stay within arms reach of someone who is experienced. This was an exciting time because it was my first time around flight operations and seeing the jets take off and land was pretty amazing. Unfortunately, within the first two weeks of me experiencing this, a man with seven or eight years of experience was killed doing the job I was training for. This was certainly intimidating and scary, but I kept going.

What were some of your main jobs/roles?

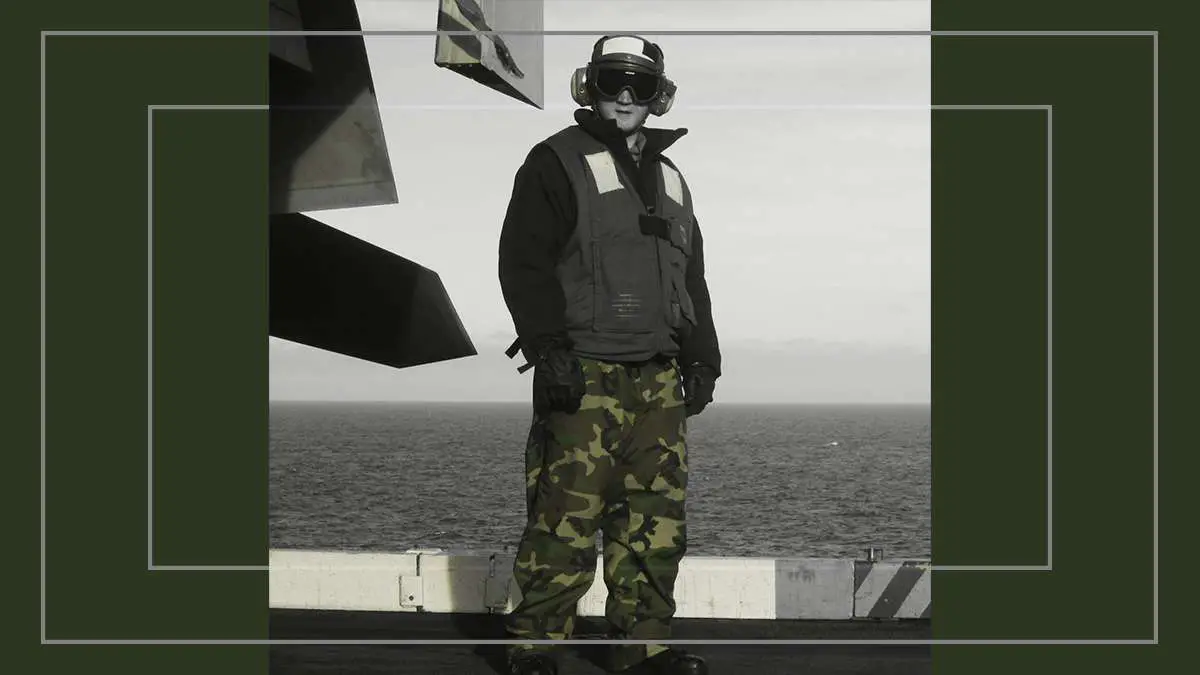

The job changed as I gained rank and qualifications. I started out as what they called “Blue Shirts” because we wore blue shirts. Blue shirts were responsible for “Chock and Chaining,” which is when a plane parks. Stoppers are placed around the tires and chains are used to secure the aircraft to the flight deck so it does not roll. It is a pretty boring job, but it is an important step in learning to work on the flight deck.

There are so many dangers that people have to look out for that starting with a simple job is useful. You have to learn how to approach the jets with propellers in a way that you don’t lose a limb; you have to learn how close is too close to the jet intakes so that you don’t get sucked in; you have to learn how to go under or around the jet exhaust so that you don’t get burned or blown down. Also, there were helicopters that posed different challenges, so it was important to start off with an easy job to learn how to navigate all these things before trying to stay safe while doing more challenging work.

The next step is tractor driving. When the planes are turned off and can’t drive on their own, we had to hook up a tractor to it and tow it around. This job is much more difficult than “Blue Shirt.” These 28-55 million-dollar jets get parked within six inches of each other and a tractor driver has to be very talented to do this with all of the other distractions going on like take offs and landings. You also have to consider that this is on a boat, so tractor drivers had to learn to adapt to ship rocking and whatever weather was going on.

If a tractor driver was towing a jet and it hit another jet it was referred to as a “crunch.” It is a really big deal if someone “crunched a bird,” which happened to me once. As I was parking a jet, the shipped rocked hard and with the rain my brakes wouldn’t stop. The nose of the plane I was parking hit another plane. It was about a $300,000 mistake. Fortunately, some people saw it and determined that it was not my fault, but it could have been bad for me.

The final stage of the job is directing. These folks were referred to as “Yellow Shirts.” Directing is the most difficult job with the most responsibility. These are the people who give directions to the pilots as they drive the jets around the flight deck, they go through all the safety checks when launching aircraft and they direct the pilots once the jets have landed. There are so many things to be aware of when directing.

Once again you can ‘crunch’ the planes, pilots can have emergencies upon landing, the plane can have problems, there is just so much going on it is difficult to explain. One simple example is with bombs, the directors have to be aware of where all the bombs are on the flight deck because if they tell a pilot to turn, the pilot has to use the accelerator which could potentially put the hot exhaust on the bombs, which, as you can imagine, is very bad.

What was your reaction to some of the places that you served, specifically to the climate/conditions/people?

So, I split time being stationed on the East and West coast. Surprisingly to some, I preferred Virginia to California. The weather was either miserably hot or miserably cold in Virginia but the built environment, people and those sorts of things suited me better. There is this really intriguing mixture of people in this area of Virginia.

The best way for me to explain it is with the bars. There were frat bars, biker bars, sailor bars, and local bars. There were large populations of college people, bikers, and sailors. None of the groups really mingled too much and there was actually occasional disputes between them. Yet, somehow we all lived in the same area mostly peacefully. That is a sociological side note but Virginia is a really cool, diverse place. California was ok. I wasn’t miserable, but it just wasn’t the same community feel.

How did you feel once you were done serving? Any sense of relief/stress/etc.?

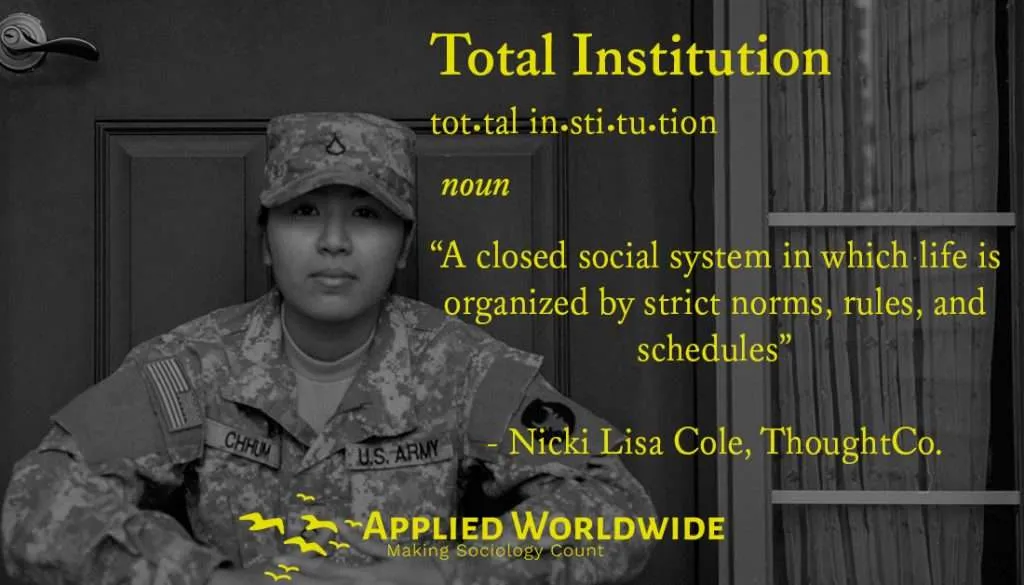

This is a really interesting question. The military is a total institution and it definitely reprogrammed me in ways that made the transition out difficult. There are so many things that people who haven’t served take for granted. Some things as simple as calling folks by their first name is awkward at first. Let alone the anxiety of not having every minute of every day pre planned. I still get anxiety when I feel like I don’t have something to do.

It is really hard to just sit and relax and enjoy the company of others. The military trains you to produce in the most efficient way, and we just don’t live that way normally. I have had to learn to really categorize work and leisure in different places in my mind because if I don’t turn off the work section, I will just work to the point that I don’t spend time enjoying friends or family. It is a really difficult thing to explain and many folks don’t really understand it, but it is one of the greatest challenges that I faced, and to a less extent still face, from my transition out of the military.

Other than that, I didn’t hate the experience and I am glad that I did it, but I am also very glad that I no longer have to do it. It was just one of those types of things.