What does the social construction of health mean?

The social construction of health and illness refers to the ways our social world shapes the assessment, treatment, and collective understanding of various diseases and health conditions. It is important for health-related organizations to view health as a social construct because the assessment and treatment of diseases and conditions depends heavily on how those diseases and conditions are socially constructed and collectively understood.

For example, how is the experience of being diagnosed with breast cancer compared to having a sexually transmitted infection (STI)? What about the diagnosis of major depressive disorder? Or Parkinson’s disease? Although there are biological differences that separate the experiences of each diagnosis, there are also cultural and social meanings attached to each condition.

The social meaning of a condition impacts how a person experiences that illness. The ways in which public discourse construct medical knowledge also impacts how society, and the medical institution, treats a particular condition.

What are the Three Main Components of the Social Construction of Health?

Peter Conrad and Kristen Barker, two well-known medical sociologists, summarize the social construction of health and illness into three key components:

- the social and cultural meanings of illness,

- the illness experience, and

- the social construction of medical knowledge.

Below, I discuss these three components within the context of breast cancer and genital herpes to illustrate how socially constructed knowledge affects the way people experience health and illness.

Breast Cancer as an Example of the Social Construction of Health

Like all illnesses, breast cancer is socially constructed. Historical context is emphasized in sociology time and time again because of the numerous ways it shapes modern day life. In the case of breast cancer, the historical portrayal of the breast cancer epidemic in the media shaped the social meaning of the illness.

For example, a sociological study by Paula Lantz and Karen Booth showed that just as women began to gain more reproductive control over their bodies, popular magazine articles discussing the breast cancer epidemic began to emerge. Many articles, while admitting that the cause of breast cancer was unknown, suggested that delays in childbirth and other behaviors of “non-traditional” women could be at fault. The researchers describe this media portrayal as backlash against women gaining more power in society.

Gendered Representations of Breast Cancer

This gendered representation of breast cancer in the media affects the illness experience of women diagnosed with breast cancer in two direct ways. First, women may suffer a loss of identity through being told that their femininity has been jeopardized by their breast cancer diagnoses.

Second, suggestions that certain behaviors could be the cause of a diagnosis places blame on women who are diagnosed. This type of self-blame has been linked to higher instances of depression post-diagnosis. The power of social definitions to enhance feelings of depression while experiencing a diagnosis demonstrates just how powerful social constructs attached to health can be.

The behavior risk factors suggested in the magazine articles also actively construct medical knowledge. Any ideas communicated through popular discourse have potential to construct public knowledge whether they are true or not. This potential for media to distribute medical knowledge to the public was shown in a 1991 study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The research shows that medical discussions in popular press amplify the diffusion of medical knowledge to the public. Based on these findings, statements about breast cancer presented as medical or scientific in popular magazines will be communicated to the public as such, therefore aiding in the social construction of medical knowledge about breast cancer.

Genital Herpes as an Example of the Social Construction of Health

The same ideas can be applied to the diagnosis of a genital herpes, a common STI. To address the social and cultural meanings of genital herpes we must, once again, discuss historical context.

According to a 1997 study by sociologist Robert Roberts, the herpes epidemic conveniently arrived at the same time as the sexual revolution. Despite research showing that it was not sexual activity but rather attitudes towards sexual activity that changed during the sexual revolution, the assumed relationship between herpes and sexual promiscuity persisted.

This simultaneous appearance of the herpes epidemic and the sexual revolution associated herpes with sexual immorality, attaching a specific social meaning to genital herpes. Because our social and cultural understandings of genital herpes assume sexual promiscuity, the experience of a diagnosis can be incredibly stigmatizing and shameful.

Many studies looking at the effect of stigma and shame on those diagnosed with such diseases have found evidence for negative psychological consequences. These negative psychological consequences present themselves in the form of distress, anxiety, lower levels of concentration, and depression. Because genital herpes can induce immense shame for those diagnosed, the illness experience is mostly defined by managing that shame.

Support groups online and offline exist with the specific goal to help those who have been diagnosed manage the shame and stigma. The need for these support groups is not based on the disease itself, but rather the social meaning of the illness that has marked those with genital herpes with a scarlet letter.

Medical Approaches to Genital Herpes

People managing the physical symptoms of genital herpes generally have two options to choose from:

- the western medicine approach, and

- the alternative medicine approach.

The western medicine approach focuses on antiviral medication that medical doctors prescribe to be taken orally.

The antiviral medication is meant to suppress physical symptoms and reduce the rate of transmission. The alternative medicine approach focuses on preventing outbreaks through diet, supplements, and stress-relief techniques. See, for example, Dr. Kelly Martin Schuh’s book Live, Love, and Thrive with Herpes: A Holistic Guide for Women These two forms of medical knowledge are based off certain social and cultural meanings attached to herpes.

Western medicine relies on the fear of transmitting a shameful virus to market their knowledge of treatment, while alternative medicine has used the idea of managing stress induced by social shame to market theirs. These two very different options for the treatment of the same disease are examples of how medical knowledge is socially constructed based on social and cultural meanings of an illness. In this instance, the social construction of medical knowledge is also influencing the treatment of the disease, once again, demonstrating the power of the social construction of health.

Why is the Social Construction of Health Important?

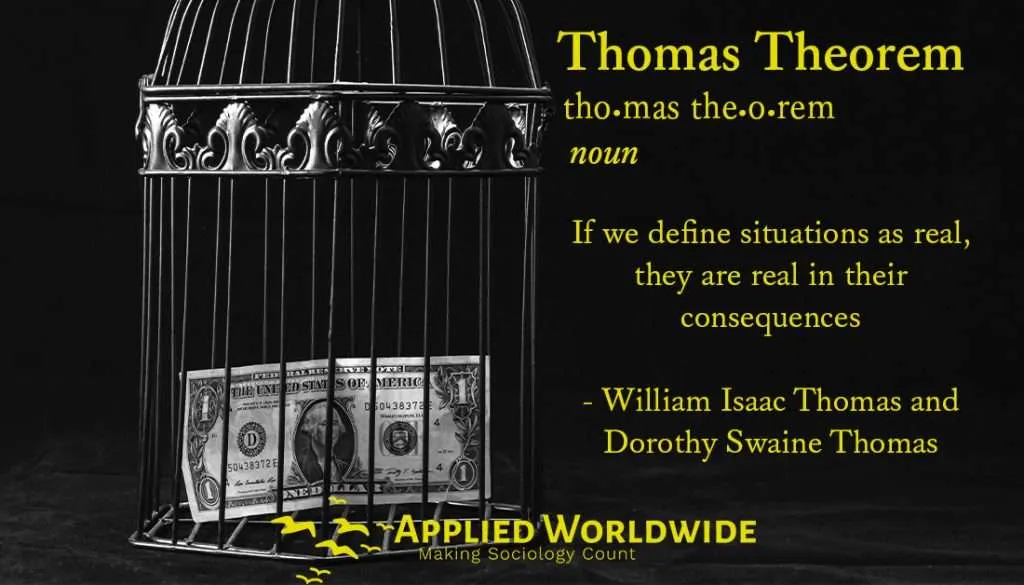

As harmless as socially constructed definitions may seem in everyday conversations, they create impactful—and sometimes detrimental—outcomes in real peoples’ lives. Just as the Thomas theorem states: “if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

The concept of social construction can be applied to other topics such as race and gender, but it is sometimes especially difficult to understand this concept when attached to something like health that seems so inherently biological, rather than sociological. For health-focused organizations, it is important to acknowledge the ways societal norms and values affect the meanings, experiences, and knowledge of illnesses so they can treat patients with the social side of health in mind.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy these!

- Medical Sociology: Applying Sociology in Health

- The Sociology of Health Care and Evidence-based Medicine

- The Social Construction of Gender and Reproductive Health