One thing we love about sociology, is it’s all around us. Every experience we have in our social world can be analyzed sociologically. Take, for instance, our recent trip to Paducah, Kentucky, a member of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Creative City Network. Simply put, this distinction has allowed a small town in Kentucky to gain some level of global notoriety for its history and expertise in the art of quilting—something we recognized as what sociologists call glocalization.

To some it may seem that this program has something to do with globalization, but the term globalization does not fully capture our experience in Paducah, nor the intended goals of UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN).

UNESCO Creative Cities Network

UCCN launched in 2004 and now has 180 member cities in 72 countries. Participating cities work towards the common mission of “placing creativity and cultural industries at the core of the development plans at the local level and actively cooperating at the international level.”

The UNESCO Creative Cities Network lists the following as its objectives:

- strengthen international cooperation between cities that have recognized creativity as a strategic factor of their sustainable development;

- stimulate and enhance initiatives led by member cities to make creativity an essential component of urban development, notably through partnerships involving the public and private sectors and civil society;

- strengthen the creation, production, distribution and dissemination of cultural activities, goods and services;

- develop hubs of creativity and innovation and broaden opportunities for creators and professionals in the cultural sector;

- improve access to and participation in cultural life, as well as the enjoyment of cultural goods and services, notably for marginalized or vulnerable groups and individuals;

- fully integrate culture and creativity into local development strategies and plans.

Each of the program objectives relates in some way to either “the local” or “the global.” For instance, incorporating different elements of the community into urban development decisions or developing hubs of creativity both seem to be addressing the locale of the cities, while “strengthening international cooperation and disseminating and distributing cultural activities and goods” seem to be addressing a global relationship.

UCCN’s objectives relating to “the local” and “the global” reminded us of George Ritzer’s work discussing the concept glocalization.

Glocalization/Grobalization and Something/Nothing

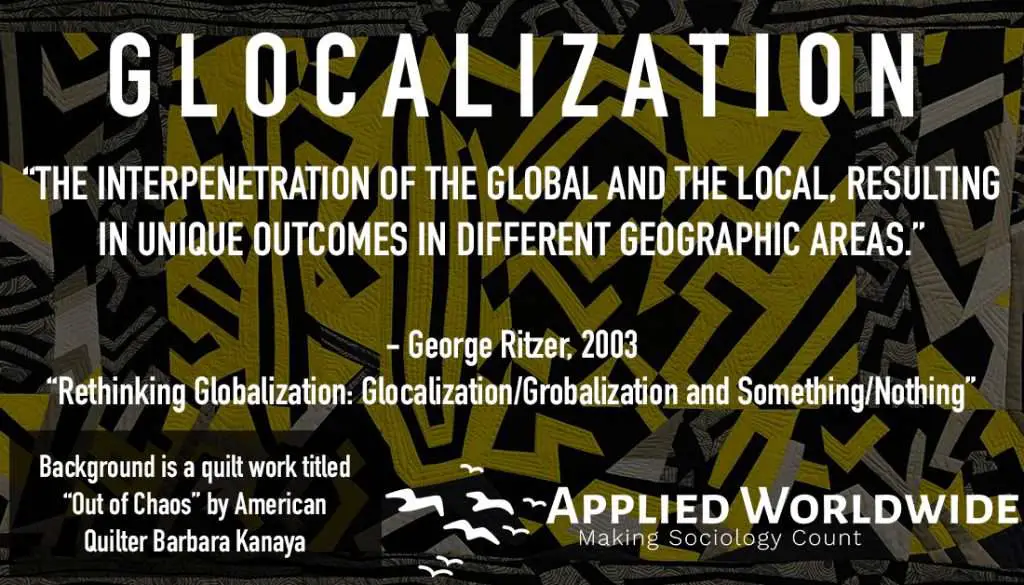

Depending on who you ask—and perhaps which country they reside in—the process of globalization may be seen as either a positive or negative change in our world. However, sociologist George Ritzer would say there is a more fruitful conversation to be had around the process of globalization. Ritzer brings necessary nuance to that conversation in his 2003 piece in Sociological Theory titled “Rethinking Globalization: Glocalization/Grobalization and Something/Nothing.”

In that piece, glocalization is defined as “the interpenetration of the global and the local, resulting in unique outcomes in different geographic areas.” Grobalization, on the other hand, “focuses on the imperialistic ambitions of nations, corporations, organizations, and other entities and their desire—indeed, their need—to impose themselves on various geographic areas.” The main interest for those focused on grobalization is “seeing their power, influence, and (in some cases) profits grow (hence the term ‘GRObalization’) throughout the world.”

The relationship of glocalization and grobalization to something and nothing is complex, but important to discuss here. Something can be understood as “a social form that is generally indigenously conceived, controlled, and comparatively rich in distinctive substantive content,” whereas nothing is a “social form that is generally centrally conceived, controlled and comparatively devoid of distinctive substantive content.” To put it more simply, something is often localized, while nothing is often globalized.

For example, you can find a McDonald’s cheeseburger almost anywhere in the world—it is nothing. But, the famous burger at the local pub named after a local hero can only be found there—it is something. Local pubs might exist throughout the globe, but the things they serve are localized and, as Ritzer would say, “rich in distinctive substantive content” making them something, rather than nothing, and glocalized, rather than grobalizaed.

The Case of Paducah, Kentucky

We started our day in Paducah, KY knowing we wanted to learn all about how the idea of a UNESCO Creative City manifested in this small city and how it relates to this global network. Our adventures started in downtown Paducah at the Visitor Center where we spoke with a friendly visitor services team member about how Paducah came to be recognized within the UCCN.

She said the journey towards joining the UCCN began with an artist relocation program that supplied cheap property for studio space in what is now known as the Lower Town Arts District. With that initiative came a vibrant creative community that only added to the already thriving folk art scene in Paducah, due in large part to a history of quilt-making. In 2013, the city decided to officially register as a UNESCO Creative City of Crafts and Folk Art.

City Murals and Sense of Place

With the designation of being a UNESCO Creative City came somewhat of a change in the city’s identity. Even if residents did not explicitly realize it, this new designation added to their quality of life in subtle, yet impactful, ways. The woman we spoke with mentioned even if residents “wouldn’t [necessarily] see it as art in their daily life,” they are still surrounded by creativity and a flourishing art community everyday.

For evidence of being surrounded by art we needed only walk a block or so from the visitor center to the river front, which is actually the intersection of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers. Along the river is a display of “Wall to Wall” Murals curated by internationally recognized artist Robert Dafford displaying the city’s historical context.

We know from sociological studies that when residents can relate to the historical context of a location, they are more likely to develop a “sense of place,” which can be valuable in community development efforts. For instance, we were told that in the summer months, Paducah has a thriving farmer’s market.

While we cannot definitively say that creating a history mural will lead to an active farmer’s market, this does provide evidence that the objectives of UCCN’s objectives are being pursued successfully in Paducah.

Quilt Museum

We continued to make observations of the city’s art and architecture until we eventually made our way to the National Quilt Museum—one of Paducah’s claims to fame. This national heritage destination is “distinguished by a longstanding tradition in the fine craft of quiltmaking” and gave Paducah the nickname, “Quilt City.” We were surprised that a nationally recognized museum is situated in a small city in the heart of America’s inland waterways, but it all made sense when we learned that Paducah is also home to the American Quilter’s Society.

We spent much of our afternoon gazing at the intricately and impressively curated quilts that lined the walls of the museum, gaining a new appreciation for an artform neither of us really knew existed prior to our visit to Paducah.

The exhibit we were especially drawn to was the COMTEPORÂNEO – CONTEMPORARY exhibit. This was a collaboration that placed American quilts and Brazilian quilts side-by-side in one unified exhibit. Visiting this exhibit was a true authentic experience. This is not a world’s-largest-ball-of-yarn type showcase, nor is this a museum exhibit that portrays life in Brazil as a monolithic experience. The imagery, patterns, and techniques used in the quilts felt somehow unique to each artist, yet fundamentally similar in that our experiences are not so foreign to one another.

The Glocalization of Something

With a connection to its history and a futuristic vision that makes quilting both a local and global experience, Paducah felt like a glocal city and is definitely something to see in a world that is—as Ritzer argues—increasingly oversaturated with nothing. With that said, as sociologists we are skeptical to make the claim that UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network is achieving its goals without more data, but this type of evaluation is a great example of what applied sociologists can provide.

Exploring Your Own Culture Abroad: An Account of an American Sociologist in Turkey