There’s no time like Christmas time, especially for capitalist countries; and with that time of year comes seasonal altruism, or the social phenomenon of increased charity during the winter holiday season.

The Christmas Spirit

Our online spaces are flooded with holiday gift ads. Retail stores set the perfect stage for consumers to buy with festive music and displays that give us all the warm fuzzies. Even our email inboxes are flooded with “deals” to get us spending more and more around the holidays. It’s not news that Christmas has become less of a Christian holiday and more of a capitalist one, but what may be news to some is how capitalism, Christmas, and the media intersect to create what some have called seasonal altruism. In popular culture, we call this phenomenon “the Christmas spirit.”

Sociological theories, as well as research providing evidence for those theories, tell us that the media has a huge impact on our behaviors and perceptions of our social world. What we see in the media gives us a basis for understanding how the world works. In fact, advertising only works the way it does because of how influential media can be. The television shows we watch, commercials we consume, and, yes, even the Christmas movies we watch, all influence us in powerful, and usually unbeknownst-to-us, ways.

The Myth of the “Good Capitalist”

I recently came across an article published by Pacific Standard discussing “The Chronic Capitalism of Christmas Movies.” The gist of the piece is that Christmas movies all include similar themes, and those themes all perpetuate the myth of the “good capitalist,” or philanthropist, according to the author of the piece, Elizabeth King. If you think about many Christmas classics (e.g., A Christmas Carol, an example used by King) there is typically a privileged character doing a good deed for someone “less fortunate” than them. Whether it’s love, toys, a Peloton, or literal capital, the spirit of Christmas is one of giving—because nothing perpetuates an economic system dependent on exploitation and inequality like giving.

You can read King’s full piece for a more in-depth look at the capitalist narrative perpetuated by Christmas movies, but what I’d like to focus on here is how that narrative drives our social behavior in immensely impactful ways. How many of you volunteered or donated food, clothing, money, or other goods in the last year? How much of those charitable acts took place sometime between November and January? It’s not merely a coincidence that many of us put our philanthropist hats on during the holidays, but it’s also not a natural biological instinct that’s driving this phenomenon. Rather, it’s a social behavior that we’ve learned through socialization from institutions like the media—including Christmas movies.

Seasonal Altruism

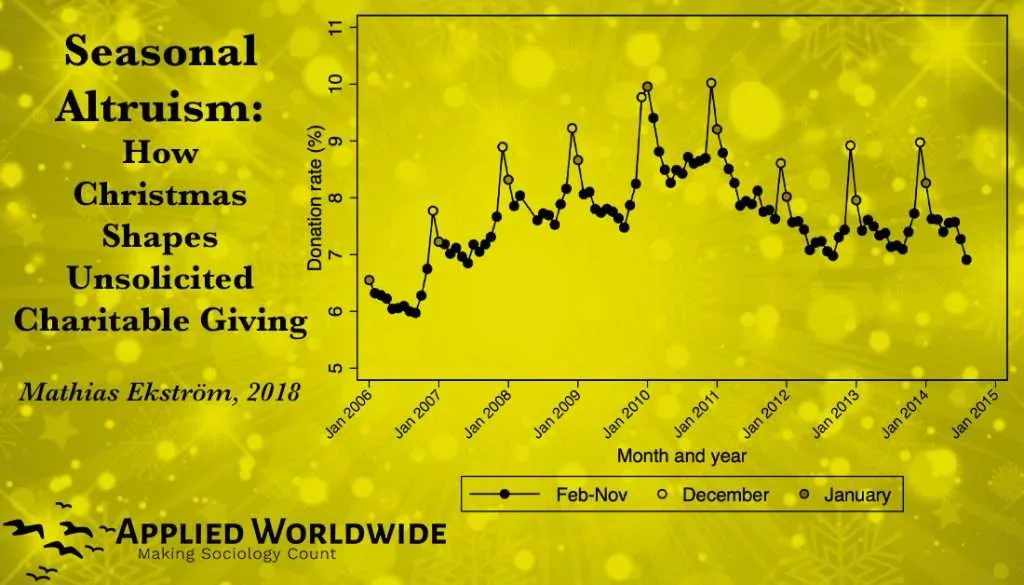

While giving, volunteering, and donating around the holidays is always necessary and helpful, this trend doesn’t come without social consequences. If we connect the dots, as economist Mathias Ekström has, we’ll see that the Christmas spirit is actually connected to a shortage of donations and volunteers in the summer months. Ekström’s research shows a huge spike in donations in the month of December, with a rapid decline throughout the rest of the year

Just this past summer (2019), there were numerous examples of volunteer shortages that had food pantries scrambling to feed those in need, including Master’s Manna food pantry in Wallingford, Connecticut. Now, we can’t simply blame the Christmas spirit and only the Christmas spirit for these shortages. Things like snowbirds leaving Arizona for the summer also contribute to both donation and volunteer shortages in the summer months. There is also the fact that many kids who face food insecurity don’t have school breakfast and lunch to feed them during the summer months, making them more reliant on food pantries. But that fact in and of itself is a great reason to nurture your Christmas spirit year round.

Taking the “Seasonal” out of Seasonal Altruism

If we let narratives in the media—such as those centered around the “good capitalist” that are rampant in Christmas movies—drive our prosocial behavior, there is a good chance our communities will suffer six month later when they’re facing those common summer shortages. The good news is, we are humans with agency who can change our behavior despite the social structures that surround us daily. Instead of letting the media socialize us into only giving over a few months of the year, we can be conscious of the fact that people who face food insecurity are facing it year-round and therefore also need support from those who can offer it year-round. With all that said, I’m challenging myself and others to take the seasonal out of seasonal altruism and let your Christmas spirit persist beyond the holidays and well into 2020.